dominican saints

St. catherine of siena, V.O.P.

Feast Day: April 30th

Born: March 25, 1347 at Siena, Tuscany, Italy

Died: April 29, 1380 of a mysterious and painful illness that came on without notice, and was never properly diagnosed

Canonized: July 1461 by Pope Pius II

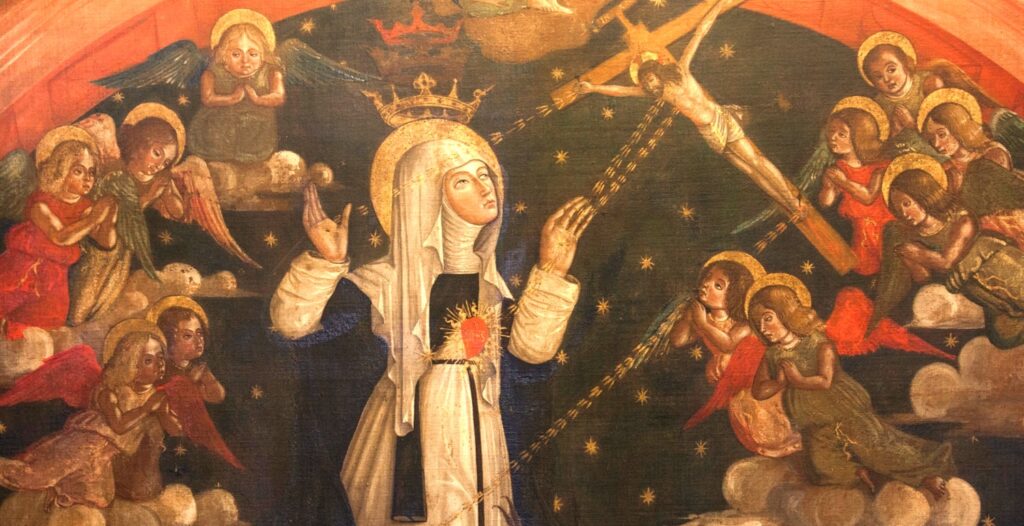

Representation: cross; crown of thorns; heart; lily; ring; stigmata

Patronage: against fire, bodily ills, diocese of Allentown, Pennsylvania, USA, Europe, fire prevention, firefighters, illness, Italy, miscarriages, nurses, nursing services, people ridiculed for their piety, sexual temptation, sick people, sickness, Siena Italy, temptations

biography

She was the youngest but one of a very large family. Her father, Giacomo di Benincasa, was a dyer; her mother, Lapa, the daughter of a local poet. They belonged to the lower middle-class faction of tradesmen and petty notaries, known as “the Party of the Twelve”, which between one revolution and another ruled the Republic of Siena from 1355 to 1368. From her earliest childhood Catherine began to see visions and to practice extreme austerities. At the age of seven she consecrated her virginity to Christ; in her sixteenth year she took the habit of the Dominican Tertiaries, and renewed the life of the anchorites of the desert in a little room in her father’s house. After three years of celestial visitations and familiar conversation with Christ, she underwent the mystical experience known as the “spiritual espousals”, probably during the carnival of 1366. She now rejoined her family, began to tend the sick, especially those afflicted with the most repulsive diseases, to serve the poor, and to labor for the conversion of sinners. Though always suffering terrible physical pain, living for long intervals on practically no food save the Blessed Sacrament, she was ever radiantly happy and full of practical wisdom no less than the highest spiritual insight. All her contemporaries bear witness to her extraordinary personal charm, which prevailed over the continual persecution to which she was subjected even by the friars of her own order and by her sisters in religion. She began to gather disciples round her, both men and women, who formed a wonderful spiritual fellowship, united to her by the bonds of mystical love. During the summer of 1370 she received a series of special manifestations of Divine mysteries, which culminated in a prolonged trance, a kind of mystical death, in which she had a vision of Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven, and heard a Divine command to leave her cell and enter the public life of the world. She began to dispatch letters to men and women in every condition of life, entered into correspondence with the princes and republics of Italy, was consulted by the papal legates about the affairs of the Church, and set herself to heal the wounds of her native land by staying the fury of civil war and the ravages of faction. She implored the pope, Gregory XI, to leave Avignon, to reform the clergy and the administration of the Papal States, and ardently threw herself into his design for a crusade, in the hopes of uniting the powers of Christendom against the infidels, and restoring peace to Italy by delivering her from the wandering companies of mercenary soldiers. While at Pisa, on the fourth Sunday of Lent, 1375, she received the Stigmata, although, at her special prayer, the marks did not appear outwardly in her body while she lived.

Mainly through the misgovernment of the papal officials, war broke out between Florence and the Holy See, and almost the whole of the Papal States rose in insurrection. Catherine had already been sent on a mission from the pope to secure the neutrality of Pisa and Lucca. In June, 1376, she went to Avignon as ambassador of the Florentines, to make their peace; but, either through the bad faith of the republic or through a misunderstanding caused by the frequent changes in its government, she was unsuccessful. Nevertheless she made such a profound impression upon the mind of the pope, that, in spite of the opposition of the French king and almost the whole of the Sacred College, he returned to Rome (17 January, 1377). Catherine spent the greater part of 1377 in effecting a wonderful spiritual revival in the country districts subject to the Republic of Siena, and it was at this time that she miraculously learned to write, though she still seems to have chiefly relied upon her secretaries for her correspondence. Early in 1378 she was sent by Pope Gregory to Florence, to make a fresh effort for peace. Unfortunately, through the factious conduct of her Florentine associates, she became involved in the internal politics of the city, and during a popular tumult (22 June) an attempt was made upon her life. She was bitterly disappointed at her escape, declaring that her sins had deprived her of the red rose of martyrdom. Nevertheless, during the disastrous revolution known as “the tumult of the Ciompi”, she still remained at Florence or in its territory until, at the beginning of August, news reached the city that peace had been signed between the republic and the new pope. Catherine then instantly returned to Siena, where she passed a few months of comparative quiet, dictating her “Dialogue”, the book of her meditations and revelations.

In the meanwhile the Great Schism had broken out in the Church. From the outset Catherine enthusiastically adhered to the Roman claimant, Urban VI, who in November, 1378, summoned her to Rome. In the Eternal City she spent what remained of her life, working strenuously for the reformation of the Church, serving the destitute and afflicted, and dispatching eloquent letters in behalf of Urban to high and low in all directions. Her strength was rapidly being consumed; she besought her Divine Bridegroom to let her bear the punishment for all the sins of the world, and to receive the sacrifice of her body for the unity and renovation of the Church; at last it seemed to her that the Bark of Peter was laid upon her shoulders, and that it was crushing her to death with its weight. After a prolonged and mysterious agony of three months, endured by her with supreme exultation and delight, from Sexagesima Sunday until the Sunday before the Ascension, she died. Her last political work, accomplished practically from her death-bed, was the reconciliation of Pope Urban VI with the Roman Republic (1380).

Among Catherine’s principal followers were Fra Raimondo delle Vigne, of Capua (d. 1399), her confessor and biographer, afterwards General of the Dominicans, and Stefano di Corrado Maconi (d. 1424), who had been one of her secretaries, and became Prior General of the Carthusians. Raimondo’s book, the “Legend”, was finished in 1395. A second life of her, the “Supplement”, was written a few years later by another of her associates, Fra Tomaso Caffarini (d. 1434), who also composed the “Minor Legend”, which was translated into Italian by Stefano Maconi. Between 1411 and 1413 the depositions of the surviving witnesses of her life and work were collected at Venice, to form the famous “Process”. Catherine was canonized by Pius II in 1461. The emblems by which she is known in Christian art are the lily and book, the crown of thorns, or sometimes a heart–referring to the legend of her having changed hearts with Christ. Her principal feast is on the 30th of April, but it is popularly celebrated in Siena on the Sunday following. The feast of her Espousals is kept on the Thursday of the carnival.

The works of St. Catherine of Siena rank among the classics of the Italian language, written in the beautiful Tuscan vernacular of the fourteenth century. Notwithstanding the existence of many excellent manuscripts, the printed editions present the text in a frequently mutilated and most unsatisfactory condition. Her writings consist of

the “Dialogue”, or “Treatise on Divine Providence”; a collection of nearly four hundred letters; and a series of “Prayers”.

The “Dialogue” especially, which treats of the whole spiritual life of man in the form of a series of colloquies between the Eternal Father and the human soul (represented by Catherine herself), is the mystical counterpart in prose of Dante’s “Divina Commedia”.

A smaller work in the dialogue form, the “Treatise on Consummate Perfection”, is also ascribed to her, but is probably spurious. It is impossible in a few words to give an adequate conception of the manifold character and contents of the “Letters”, which are the most complete expression of Catherine’s many-sided personality. While those addressed to popes and sovereigns, rulers of republics and leaders of armies, are documents of priceless value to students of history, many of those written to private citizens, men and women in the cloister or in the world, are as fresh and illuminating, as wise and practical in their advice and guidance for the devout Catholic today as they were for those who sought her counsel while she lived. Others, again, lead the reader to mystical heights of contemplation, a rarefied atmosphere of sanctity in which only the few privileged spirits can hope to dwell. The key-note to Catherine’s teaching is that man, whether in the cloister or in the world, must ever abide in the cell of self-knowledge, which is the stable in which the traveler through time to eternity must be born again.

Prayers/Commemorations

First Vespers:

Ant. This day is sacred to the honor of the Virgin Catherine, that the excellence of such great sanctity may never fade from the memory of men, but may be ever held by all in highest esteem, alleluia.

V. Pray for us, Blessed Catherine, alleluia.

R. That we may be made worthy of the promises of Christ, alleluia.

Lauds:

Ant. Of the highest excellence is Catherine, the Virgin of Siena, who was able to restore health to the infirm and life to the dead, alleluia.

V. Virgins shall be led tot he King after her, alleluia.

R. Her companions shall be presented to Thee alleluia.

Second Vespers:

Ant. O most glorious Virgin, whose festival the whole world celebrates this day, whom the angels praise and the others heavenly citizens admire , obtain from God that our minds may be always submissive to the divine commands, and that we may advance in virtue and in all goodness, alleluia.

V. Pray for us, Blessed Catherine, alleluia.

R. That we may be made worthy of the promises of Christ, alleluia.

Let us Pray: O God, who didst enable Blessed Catherine, graced with a special privilege of virginity and patience to overcome the assaults of evil spirits, and to stand unshaken in the love of Thy holy name, grant, we beseech Thee, that after her example treading under foot the wickedness of the world and overcoming the wiles of all enemies, we may safely pass onward to Thy glory. Through Christ our lord. Amen.

Octave of Saint Catherine of Siena

Lauds:

Ant. May Catherine, the Virgin blessed, give us the enjoyment of the true light of Christ and unite us to the heavenly choirs, alleluia.

V. Virgins shall be led to the King after her, alleluia.

R. Her companions shall be presented to Thee, alleluia.

Or, on feasts of other Virgins:

V. God will aid her by His countenance, alleluia.

R. God is in the midst of her, she shall not be moved, alleluia.

Vespers:

Ant. May the Virgin Catherine, cherishing us by her merits, lead us to the throne of the heavenly kingdom, alleluia.

V. Pray for us, Blessed Catherine, alleluia.

R. That we may be made worthy of the promises of Christ, alleluia.

Novena to ST. Catherine of Siena

O marvelous wonder of the Church, seraphic virgin, Saint Catherine, because of your extraordinary virtue and the immense good which you accomplished for the Church and society, you are acclaimed and blessed by all people. Oh, turn your benign countenance to me who, confident of your powerful patronage, calls upon you with all the ardor of affection and begs you to obtain, by your prayer, the favors I so ardently desire.

You, who were a victim of charity, who in order to benefits your neighbor obtained from God the most stupendous miracles and became the joy and the hope of all, you cannot help but hear the prayers of those who fly into your heart – that heart which you received from the Divine Redeemer in a celestial ecstasy.

Yes, O seraphic virgin, demonstrate once again proof of you power and of your flaming charity, so that your name will be ever more blessed and exalted; grant that we, having experienced your most efficacious intercession here on earth, may come one day to thank you in heaven and enjoy eternal happiness with you. Amen.

St. Catherine of Siena

Saint Catherine was born at Siena in Tuscany, April 30 A.D. 1347. Her father, James Benincasa, was a dyer of that city and she was the youngest of his numerous family. Whilst still a little child she attempted to retire into solitude, in imitation of the Fathers of the Desert, and at the age of seven she consecrated herself to God by a vow of virginity. When she grew older her parents endeavored to persuade her to marry and the Saint had to undergo much domestic persecution on this account, all which she bore with invincible patience and constancy. At length her father became convinced that her resolution was from God, and gave orders that she should no longer be opposed in her pious designs. She spent some years in a life of strict retirement and at the age of about seventeen took the habit of the Third Order of Saint Dominic, being, it is said, the first unmarried woman who had ever been received into that Sisterhood. She continued, however, as before, to live in her father’s house, devoting herself to exercises of prayer and the practice of severe austerities. It was the Divine will that she should be tried by grievous temptations, over which her humility and unshaken confidence in God enabled her to be always victorious. She was miraculously taught to read and write and Our Lord deigned often to recite the Office with her in her little chamber.

On the last day of the Carnival, A.D. 1367, she was visibly espoused to our Divine Lord, and some years later He vouchsafed to her the mysterious favor of the exchange of hearts and the impression of the sacred Stigmata. After her espousals she began to come forth from her retirement and to take part in the household duties. Our Lord had taught her to seek and find Him in His two chosen dwelling-places the Sacrament of His love and the person of His poor.

She was accustomed to approach the Holy Table very often, at a time when frequent Communion was by no means common; her influence and example are said to have largely contributed to the revival of this salutary practice. In accordance with her own maxim, that “the love we conceive towards God we must bring forth in acts of charity towards our neighbor,” she began to practice the most heroic services of charity. Her self-devotion was on more than one occasion repaid only by the blackest calumny and ingratitude; but her sweetness and patience triumphed, and her persevering prayer won back her persecutors for God. Marvellous conversions were granted in answer to her fervent supplications and she had an extraordinary power over the evil spirits, whom she often drove from the bodies of the possessed.

The sphere of her influence gradually widened as her sanctity made itself more and more apparent. She was called upon to heal the terrible feuds which were the bane of Italy in the Middle Ages, to urge on the undertaking of a fresh Crusade against the infidels, and to become the counsellor of Popes, Cardinals, and Princes. The Florentines had revolted against the Holy See, and, fearing the consequences of their rebellion, they entreated the holy maiden of Siena to plead their cause with the Sovereign Pontiff. For this end she visited Avignon, where the Papal Court then resided, and whilst there succeeded in persuading Gregory XI to return to Rome. The Saint went back to Florence as ambassador from the Pope, and April 30 after much trouble and persecution succeeded in effecting a reconciliation between that city and the Apostolic See. She dictated some sublime treatises whilst in a state of ecstasy, and they were afterwards published under the title of the “Dialogue.” A great number of her letters to persons of all classes and conditions have also been preserved; they are full of the most beautiful and practical instructions in the spiritual life.

Saint Catherine greatly exerted herself to maintain the authority of the Holy See during the unhappy schism which followed on the death of Gregory XL His successor, Urban VI, summoned her to Rome towards the close of the year 1378 that he might be assisted by her wise counsels. The remaining seventeen months of her earthly pilgrimage were spent in the Eternal City. There she prayed, and suffered, and finally offered her life as a victim for the Church and its visible Head, “the Christ on earth,” as she loved to call him. The sacrifice was accepted; and after many weeks of agonizing suffering, both of body and soul heroically endured, she departed to her Spouse on Sunday, April 29, A.D. 1380. She was canonized in the year 1461 by Pius II., himself a native of Siena, who wrote her Office with his own hand.

We cannot better conclude this brief notice than by quoting two of Saint Catherine’s favorite maxims which were taught her by our Lord in these words: “Thou must not love Me, or thy neighbor, or thyself, for thyself; but thou must love all for Me alone; ” and again, ” Make in thy soul as it were a little spiritual cell, closed in with the material of My Will . . .which must so encompass every faculty of thy body and soul that thou shalt never speak of anything but what thou deemest pleasing to Me, nor think nor do anything but what thou believest to be agreeable to Me.”

“Short Lives of the Dominican Saints” (London, Kegan Paul, Trench, and Trübner & Co., Ltd., 1901)

meDITATION

St. Catherine of Siena said: “All the way to heaven is heaven, for He said, ‘I am the way.’”

“Thou hast loved justice and hated iniquity,” Psalm 44:8.

I. The many trials, temptations, and labors of St. Catherine of Siena are a matter of history; yet her letters and prayers joyously proclaim time and again her realization of heaven on earth. This is the valley of tears only when we leave God’s presence voluntarily by sin. Catherine, who lived each moment in God and for Him, found heaven everywhere. This is what God wills in creating all men for Himself, that the joy of earth become a preface to eternal happiness.

We can measure our distance from sanctity by our failure in simplicity, by our lack of singleness of purpose. Life, even religious life, is not so much a daily martyrdom as it is a daily renewal of the privilege of walking with Christ. We were created by God for the happiness of His continual companionship. If we abuse the joyous privilege of His presence, we must expect unhappiness and its consequences because we have complicated our existence by sin and have ignored the single purpose of that existence.

“The dwelling in Thee is as it were of all rejoicing.” Psalm 86:7.

II. St. Catherine’s life is replete with instances in which she took Christ at His word. It was enough for her that He said: “I am the way.” John 14:6. She followed that way herself and pointed it out untiringly to others: to popes, princes, servants, friends, and even criminals. He had said: “I am come to cast fire on the earth” (Luke 12:49); and Catherine, taking these words to heart, became a flame burning with love and consumed herself in His service.

We expect our words to be respected and to influence others, yet we scarcely heed Christ’s most direct words to us. When we do recall what He has said, we sometimes soften His meaning for our own ease, or argue against the simplicity of taking Him at His word. Let us henceforth be sincere with Our Lord and accept in their exact significance the directions for sanctity He has given us. “Speak, Lord, for Thy servant hearth.” 1 Kings 3:9.

III. Physically in her bodily mortifications and suffering, intellectually in her keen pursuit of truth, and spiritually in her utter abandonment to God’s will, St. Catherine identified herself with Christ. He was the way, so she would be the wayfarer. Christ was all; Christ was beatitude: Catherine was in heaven.

Christ is the way that we, too, profess to have chosen; yet perhaps we go our own way, the loveless, unhappy way of self in pursuit of bodily comfort, intellectual sloth, and spiritual tepidity. We find no heaven, as we should, because we do not identify ourselves with Christ, who is the way. “No man cometh to the Father, but by Me.” 6 John 14:6.